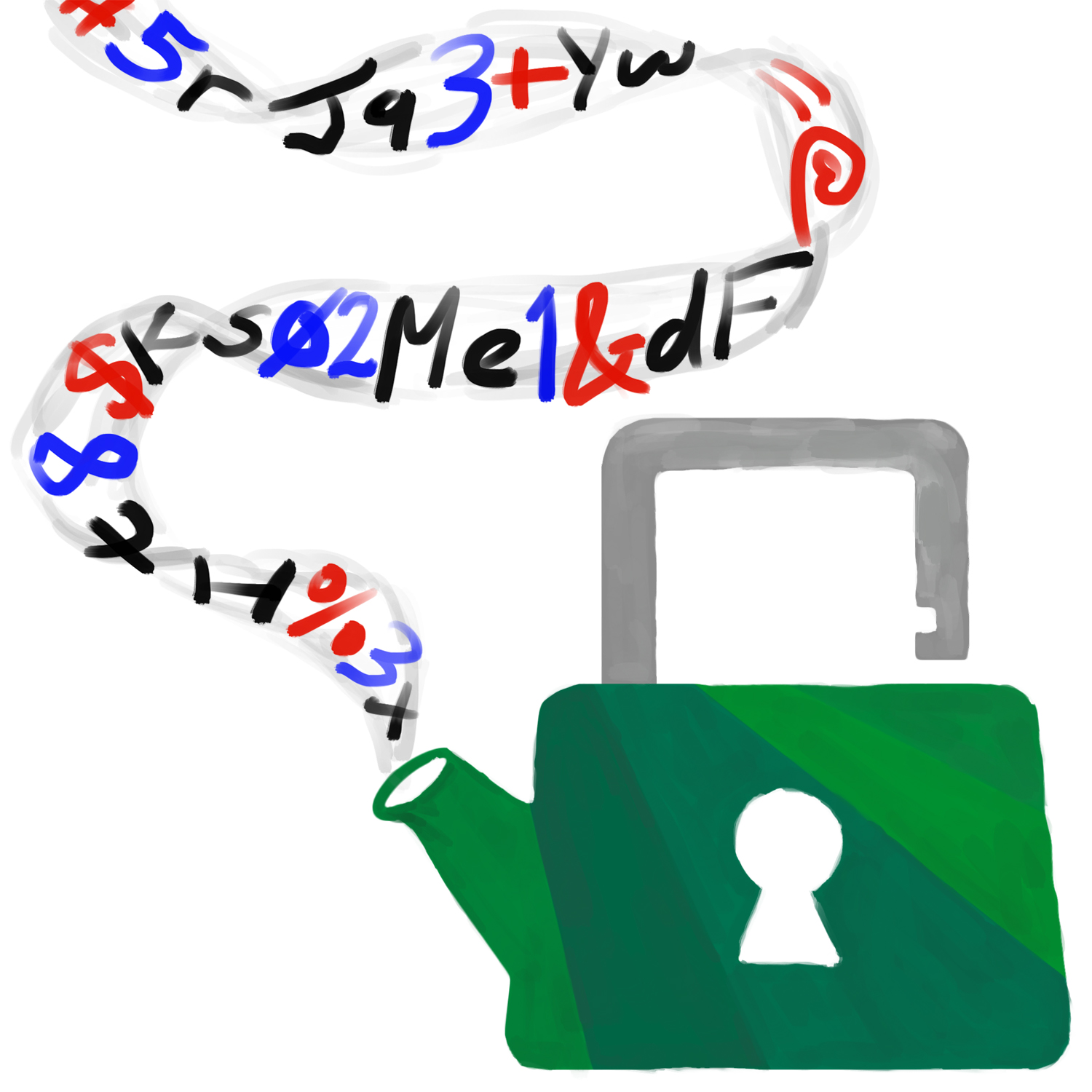

You've heard for years about how to come up with strong passwords, but are those guidelines really true? Liz and Geoffrey talk about new risks to your online accounts, especially with the news of clear-text passwords being mishandled at Twitter and GitHub, and whether you should trust a password manager to solve all your password problems for you. Plus, what's happening to the green lock icon in Chrome, and should you worry about EFAIL?

Timeline

- 0:42 - Security news: Google Chrome's changes to security indicators

- 3:35 - Security news: EFAIL

- 5:34 - What makes an online account password strong?

- 15:20 - Password managers

Show notes & further reading

Generating passwords

Making a secure pass-word is hard. For something that's easy to both generate and remember as a human, you're better off generating a pass-phrase of a few random words. If you use a long enough passphrase, you don't need to bother with capital letters or symbols (which don't contribute very much additional randomness to your password compared to adding an extra word).

The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a non-profit group dedicated to digital rights and privacy activism, has a page on generating passwords by rolling dice and looking up words in a list based on those dice rolls. A secure passphrase generally involves rolling five 6-sided dice six times to select six words.

The randomness ("entropy", in computer science jargon) of picking words out of a physical dictionary is hard to estimate. We tried flipping through a dictionary and found ourselves stuck on the same 300 or so pages repeatedly, and practically speaking, we were most likely to pick the one of the more interesting words on a page we landed on. So that's maybe as strong as three, possibly four dice rolls. Five words picked in this way would be a medium-strength password - it will be fine for temporary use, but you shouldn't use this for, say, your long-term master password for your password manager.

If you're a Python user, Horsephrase is a good option for generating strong, but memorable passwords. Horsephrase picks five words from a longer list than the EFF dice roll method above. Because it's software, make sure to run it on a reasonably trustworthy computer.

Using a password manager (more on those later in these notes) is of course also a great choice, but it might not generate random memorable passwords.

Password leaks and breaches

Sometimes, a website will unintentionally release your secure information, possibly including your account's password. We call that event a breach.

If you hear about a breach, you should update your password for that site, whether or not that site says your account information was among the information leaked. You should also update your password for any other online accounts where you use that same password or something similar to it.

Tell your friends about the breach, too, because they might have missed the notification or might not have been notified at all. Also, encourage them to update their passwords.

"Pwned" is hacker-speak for "defeated" or "compromised" and is often used when casually talking about password breaches. The Have I Been Pwned website, run by security professional Troy Hunt, tracks breaches and compromises of websites that leak personal information, and you can see which known breaches have involved your email address there. In some cases, these breaches only include email addresses, which you may be less concerned about (for instance, our email addresses are both public anyway), but if you see "Compromised data: Passwords," you should definitely make sure you've changed your password. You can also sign up for future breach alerts: if your email address is ever seen in another known breach, you'll get an email.

Password managers

Update: We have a new password manager reference page, which includes a comparison of popular password managers that we will be keeping up to date periodically. The following information was our thoughts at the time of this episode release in May 2018 and may be outdated or incomplete compared to the new reference page.

The top four contenders these days (in alphabetical order) are 1Password, Dashlane, KeePass / KeePassXC, and Lastpass. We have not tried all of these ourselves, and you may also want to check out reviews from Lifehacker or Wirecutter.

Browser extensions are a little bit less secure than desktop apps, because they're more exposed to attacks from the web. However, desktop apps often want you to copy/paste passwords, which is risky, and they're also also less convenient than an extension, so you may be less likely to use it reliably. We think most of our listeners will want to use a browser extension.

Some password managers support automatic password changes, where they know how to log into popular websites and change your password for you (and automatically store the new, auto-generated password). It's a little gimmicky, but convenient. Some also support an emergency access feature, where you can designate someone you trust to request access to your passwords. Once they make a request, you'll get a notification and have some time (e.g., a day or two) to object. This ensures they can get access to your accounts if you're incapacitated, but if you're able to respond, you aren't giving them (or anyone who breaks into their device) access.

A few claim to offer two-factor authentication. Since a password manager isn't really an online service, the definition of "two-factor" is a little fuzzy. Usually it means that their cloud sync service requires the "second" factor to give you access to the encrypted file, which is protected by your master password. Sometimes it means that the encryption for the file depends both on your master password and on a key on a thumbdrive or hardware token. This model is stronger, but losing your second factor means permanently losing access to all your passwords, same as with forgetting your master password. As a reminder, this is one of the good reasons to keep your email password outside of your password manager - you would still be able to recover your online accounts via email password resets if this happened.

1Password has no free offering; their basic account is $36/year. Sharing requires the "Teams" plan, $48/year, or the Families plan, which is 5 licenses for $60/year. They have a web interface for your passwords, which is a little less secure than an app (even though decryption still happens on your computer), but they also have desktop apps for Windows and macOS. Linux users can get a command-line tool but not a full app.

1Password is currently unique in supporting a "travel mode" that removes all your passwords except the ones marked "safe for travel," primarily to protect you when searched at international borders. You can turn this on and off from the website only.

- Mobile apps: Android and iOS

- Browser extensions: The older extension, which requires the desktop app, supports Chrome, Firefox, Safari, Opera, and Edge. Their newer one, "1Password X", requires current versions of Firefox or Chrome and works without the desktop app (so it works on Linux and on Chromebooks) but doesn't quite have all features.

- Sharing: Yes, by creating a shared "vault". Sharing requires a Teams or Families account.

- Automatic password change: no

- Emergency access: no

Dashlane's free offering does not support password sync across multiple devices (the encrypted file is only stored locally), but has most other features you'd expect. A Premium account is $40/year. Dashlane works either via desktop apps on Windows and Mac, or via standalone browser extensions that do not require the app installed.

- Mobile apps: Android and iOS.

- Browser extensions: Chrome (including Chromebooks) and Firefox.

- Sharing: If both users are on the free plan, they can share and synchronize up to 5 items. Premium users have unlimited sharing.

- Automatic password change: Yes, currently only on the Windows, Mac, and iOS apps. You can also bulk-change several passwords.

- Emergency access: yes

KeePass and KeePassXC are both free / open-source software options, which we're generally sympathetic to (especially for security / cryptographic software), but the polish isn't quite as good as with the commercial options. If you're running Linux and/or you're a free-software person yourself, this is probably one of your better options. If not, it will be easier to get sync, browser extensions, mobile apps, etc. working with the other, commercially-supported products.

KeePassXC is the EFF's suggested password manager.

KeePass has been around since 2003, but originally supported Windows only. There was a cross-platform rewrite called KeePassX, which was abandoned last year and is now maintained by another team under the name KeePassXC. It supports all of Windows, macOS, and Linux well (packages are in all major Linux distros). KeePass itself now uses .NET so you could run it with Mono on other OSes, but that's somewhat involved.

- Mobile apps: There are unofficial apps for Android, iOS, Windows Phone, Blackberry, and many others; see KeePass's long list of recommendations and KeePassXC's shorter recommendations

- Browser extensions: KeePassXC-Browser works in Firefox and Chrome, but it requires a desktop app. On a Chromebook, try Tusk, which is read-only. KeePass has an overwhelming number of suggestions on their 2003-era web page, none of which look obviously right.

- Sync: KeePassXC has no built-in sync; they recommend using your favorite cloud storage tool (Dropbox, Google Drive, etc.) to synchronize the encrypted file. KeePass has built-in sync but it looks complicated (and for security software, "complicated" is usually not great).

- Sharing: DIY, you can sync another database with friends/family and share its master password.

- Automatic password change: no

- Emergency access: no (no online service to attempt to contact you and enforce the waiting period)

LastPass has a free account and a $24/year premium option with a few more features like better sharing and encrypted file storage. You can also get "LastPass Families" with 6 premium accounts for $48/year.

LastPass primarily works via browser extensions, which are supported on all platforms, but there is also a Mac desktop app.

- Mobile apps: Android, iOS, and Windows Phone.

- Browser extensions: Chrome (including Chromebooks), Firefox, Safari, Opera, and Edge.

- Sharing: The free account lets you securely send individual passwords (but not update them). Premium lets you synchronize shared folders.

- Automatic password change: yes, in beta, one at a time, via the Chrome and Safari browser extensions only.

- Emergency access: yes

In the news

Chrome has a blog post, "Evolving Chrome's security indicators", about their plan to remove the "Secure" indicator and the green lock on HTTPS pages, and instead add a "Not secure" warning and a red danger symbol to HTTP pages.

The EFAIL website goes into technical detail about the vulnerability. There's a good post on the ACLU's blog by their senior staff technologist Daniel Kahn Gillmor, who has also been active in the PGP community for many years, including as a contributor to the widely-used GnuPG implementation. His post includes both practical steps for email security and philosophical discusson of how we should think about the risks and troubles of secure email.

For person-to-person messaging where you're comfortable sharing phone numbers, we strongly recommend the use of Signal's mobile apps for encrypted messaging, although it's more of a texting / IM model than an email model. Unfortunately, Signal's desktop apps have also been in the news recently for vulnerabilities, so we can't recommend them.

Transcript

Intro music plays.

Liz Denys (LD): Hello and welcome to Loose Leaf Security! I'm Liz Denys,

Geoffrey Thomas (GT): and I'm Geoffrey Thomas, and we're your hosts.

LD: Loose Leaf Security is a show about making good computer security practice for everyone. We believe you don't need to be a software engineer or security professional to understand how to keep your devices and data safe.

GT: In every episode, we tackle a typical security concern or walk you through a recent incident.

Intro music fades out.

LD: Today we're going to focus on online account passwords in light of two recent incidents at Twitter and GitHub which exposed some users' passwords to company employees.

Before we get into our main discussion on passwords, let's touch on a couple of other security things currently in the news. First, Google's Chrome browser is changing up how it displays sites that are fully using the secure HTTPS protocol versus sites that still have some HTTP elements. HTTP is the original, unsecured protocol that your web browser used to request and display webpages, and all its requests are in plaintext. Plaintext means that anyone who is on the way between your computer and the website that you're wanting to load can see what you're saying - so anyone who's on your home wifi, that person who runs the network at the hotel or coffee shop you're logged into, your IT department at work, and so forth. This isn't very secure because someone could intercept these requests and maybe even give your browser some fake responses, so instead of loading your bank's webpage, it might load a webpage that looks just like your bank but actually isn't talking to your bank at all. That could be really scary if you're trying to move some money around in your bank accounts. HTTP Secure, or HTTPS for short, is an improved, encrypted version that ensures that you're really talking to your bank and that no one else is listening.

GT: So right now in Chrome, or any other web browser really, when you load a fully HTTPS site, the kind of site you want, the address bar shows a green lock and says "secure". You're probably used to looking for that green lock. If a site has any of these less secure HTTP elements, or if the whole thing is just over unsecure HTTP, it doesn't say anything; it has a grey "i" in a circle by it that you can click on for more information. When you click on that, Chrome warns you "Your connection to this site is not secure" and that you should not enter passwords or credit card numbers because at least part of this website is going over an unencrypted, less safe connection. Google's plan is to have Chrome stop marking sites that fully use HTTPS as secure with a green lock and just not show anything for those sites. But, for sites that have these less secure elements, it's going to prominently display the words "Not secure" in red and a red warning icon right in the address bar.

LD: This is a really great improvement. The current warning isn't as in-your-face as the new red "Not secure" is going be, right there in the address bar. I think more people will be aware that the connection that they're on isn't secure, and they'll think more carefully about whether or not they want to give sensitive information like credit cards over on those sites.

GT: Yeah, and it's also just a more sensible model of security, I think. When Chrome is saying a website is secure, all it's really saying is that the connection from your computer to that website is secure against anyone else. It doesn't know if the website itself has been hacked. It doesn't know if it's a phishing site or malware or just not the same bank you were thinking of or whatever. It's a lot better for Chrome to tell you the things that it really knows. So if it knows that a site is insecure in this way, it'll give you a warning, but it's not going to promise that it's secure when it doesn't really know.

Interlude music plays.

LD: A second security thing that's in the news lately is EFAIL, which is a particular vulnerability related to PGP and S/MIME encrypted emails. I almost didn't really want to bring this up because it's kind of a niche issue, but since there's a lot of coverage out there and a lot of it's really confusing, let's touch on it briefly.

GT: So, EFAIL is about two types of email encryption: one method is called PGP and the other is called S/MIME. Very few people encrypt their email with PGP - we'll talk about email security in a later episode, but the sad truth right now is that if you want encrypted email, there aren't a lot of good options today. S/MIME is really popular for encrypted email with companies or with the government, and if you're an IT admin at a company or with the government, this matters to you a lot and probably you've already done something about this. But if you're just someone who's checking your personal email and just using company email, this shouldn't be something you're going to be dealing with directly.

LD: Yeah, someone at your company is already figuring out how to deal with it and telling you what to do to fix it. If you are dealing with this personally, you should make sure to use plaintext with encrypted email, because EFAIL only affects HTML email, and start encrypting and decrypting your email manually.

GT: I do know a couple of people who are in that very small minority that uses PGP for encrypted emails, and most of those people are already using pretty locked down, text-based clients because they've been worried about attacks just like this, which just affect you if you're using HTML email and loading images and so forth.

LD: Yeah, and if you are using this and you're not using those locked down, text-only type of setups, you can also get around this issue by switching to other secure messaging system like Signal in the meantime. Instead of talking about this a lot more, we'll just include a few extra links along with this episode's transcript at looseleafsecurity.com.

Interlude music plays.

LD: Alright, let's get to the main topic of this episode: online account passwords. I specifically say "online account passwords" because the security concerns aren't the same as with your personal computer's password.

GT: We'll definitely be talking about passwords for your laptop or for your cell phone in a future episode and how to secure your devices in general. But those are two very different kinds of risks. One is that someone has some physical device that you're supposed to have, and the other is that someone from anywhere on the internet might be trying to log into your account.

LD: Yeah, also what you're worried about is going to be different than with your laptop. You know, maybe someone will get into an online shopping account you have and order a bunch of things, and that website isn't going to make them re-enter your credit card number before going through. Or maybe, you know, they're going to get into somewhere where you store all of your photos, and you don't have those locally on your computer anymore, and someone might delete them and you might lose years of family photos, vacation photos, that video when your child first walked.

GT: Yeah there's a lot of possible things you might lose.

LD: And someone could also just get into your social media accounts and then impersonate you or say really negative things about your friends or say something that's going to get you in trouble at work. There's a lot of possible problems that can happen.

GT: That's a really good concern.

LD: And also the other thing is not only is what the website is currently used a potential problem, but websites are often evolving, especially social media sites. So even if a website, right now, doesn't seem like you're going to lose a lot if someone gets in, that could change in a few years. My go-to example for this isn't exactly social media, but when Gmail came out in 2004, the account you made with it was really just for a new email service, but now it has an affiliated calendaring account, hangouts chat, YouTube, Google Drive for storing files in the cloud, and someone could really turn that account into something totally different than what you had back in 2004!

GT: Oh, absolutely. When I signed up for Gmail, I wasn't thinking, "This is going to be the account I use for everything". For instance, I used to have an Android, and Android wants you to sign up with your Google account, which is super different from this mail service you just signed up for offhand ten years ago.

LD: Yeah, and that's why security people are so obsessed with thinking about security for every single online account you make. Not to fear-monger too much, but you never know what might go wrong a little bit down the road.

Now that we've talked a little bit about why you should care about securing your online accounts, let's talk about what sort of attacks might happen and how you can work to prevent them. I personally find it a lot easier to actually do the best practices when I understand why I should be caring about it, and I also don't really like the common rules that people throw around that are kind of fast and hard and they're a little oversimplified. Then people don't really know what kind of background makes those rules actually be useful.

GT: The advice you've probably heard is don't use short or very guessable passwords like "rainbow" or "123456" or "password123," which is still very good advice, but websites usually stop you from creating simple passwords. They've got rules on how long it has to be, on how complex it has to be. Also, there are large lists of common passwords, and many websites will check your passwords against these lists right when you try to sign up with one of those passwords.

LD: The other common advice is not to use personal information like your partner or your dog's name. Websites aren't really going to know, necessarily, to prevent you from using them, but it's very easy information to find. And especially now that there's social media and people have all of this information stored there, you don't even necessarily need to be close to someone to know who their partner is or what their dog's named.

GT: So definitely, you don't want to use something that an attacker can just guess if they want to get into your account because they'll just try that.

LD: A lot of people will try to obfuscate those sorts of passwords by what they think is cleverly capitalizing only some letters or adding a couple numbers at the end or maybe even in the middle, but attackers know that strategy, too. More secure passwords have more "randomness" in them. There is actually a pretty good way to generate secure passwords by rolling dice and using those dice rolls to select words out from a long word list. We'll include a link to this method in our episode notes on our website.

GT: So, this is all the classic advice about passwords, and it's all still very valid. But we're now seeing more sophisticated attacks where websites that are storing personal information are getting breached, and in these breaches, they exposed this personal information to attackers, and sometimes that includes email addresses and actual passwords or something that will let people determine very easily what the actual passwords were.

LD: Yeah, and that's the worry with what happened a couple weeks ago with Twitter and GitHub passwords. It's worth noting that in both of these cases, logs of the plaintext, raw passwords were only exposed to company employees, so it hasn't become a full public breach yet. But once those passwords are logged somewhere, it's a much higher a risk that they'll just get out and get logged somewhere else.

GT: Right, probably their employees aren't setting out to do anything bad, although you never know. But it's really hard once something has been logged, once something has been written to disk, to make sure that it never gets out to a wider group of people. You might dispose of those hard disks without cleaning them properly. You might keep backups and might have legal requirements to hold onto backups for some amount of time. It's actually not simple at all, once something has been recorded, to make sure it never leaves the company.

LD: And once those passwords do get into bad hands, attackers are definitely going to exploit them. They're going to try it both on Twitter and GitHub, and then on any other websites, too, they want to get into because you might have reused those passwords.

Let's actually back up a tiny bit, and talk about how they got there in the first place. GitHub was accidentally logging them on password reset over some period of time, and Twitter didn't specify how they got in logs, so we should assume that all passwords show up in those logs.

GT: I just want to talk a quick bit about logging, and it's a perfectly normal thing you do when you're writing a website and you're a big company and you have the room for it: just record everything that happens, so that if something goes wrong, you can go and see what was the page they were trying to load, what were the parameters. And ideally, when you're doing this logging, you exclude passwords, because the only time you really want to be seeing clear passwords and storing them is when you're creating a new account or updating the password for an existing account. And in those cases, you want to store them in a one-way encrypted form where you don't have the cleartext of the passwords. But they were just not doing that in these cases and just storing whatever data was being passed when people were logging in.

LD: And also, sometimes these logs are used to help secure your accounts. If they see a lot of failed login attempts, then they might block that IP for a while because it's probably an attacker trying to get into your account and not you just repeatedly messing up your password.

GT: Right, so it's perfectly legitimate that they are storing some logging information from login attempts. But now that these passwords have been logged as part of those records and those records are somewhere internal to these companies, there's a big risk, like we was saying earlier, that it might get out elsewhere.

LD: And attackers love to get their hands on these password lists, which probably in these cases even link the password specifically to the email address or username on the account. So they can trivially try that exact same combination on these websites and on any other website, which is why it's really important to have unique passwords for every online account you have.

GT: Every time you see one of these breaches, you're going to want to update your passwords, not just on that site, but on every site where you might have the same password or something similar, both slight spelling changes and password schemes.

LD: Oh, password schemes were so popular a while ago, like if you use something like DolphinTwitter121* for Twitter, and DolphinFacebook121* for Facebook. An attacker can also clearly see your scheme of Dolphin, whatever the website is, 121*, and anywhere you use that scheme, you need to update that password.

GT: Right, so, I started using, several years ago, a scheme, and I've been moving away from it, and I need a good place to store all these completely random, unrelated passwords that I have for every website now.

LD: Yeah, but before we get into that, let's talk about how to know when a breach has happened. I knew about the GitHub breach because my account was specifically one of the accounts that was definitely in the breach, and I saw the Twitter one first in a tweet and then in a vague suggestion to consider changing my password when I opened the Twitter app on my phone. But I actually have like six Twitter accounts, and only one of them showed me any sort of warning.

GT: Yeah, if you hear about a breach, you should probably go ahead and update your password, whether or not the website explicitly tells you that you need to do so.

LD: And to update your password, I don't recommend clicking a link in an email about the breach, like the one I got from GitHub. You know, while that was an actual email for GitHub, it could have just been someone trying to phish my account as well. So it's a lot safer to login and change your password the normal way, or if your account is locked like GitHub did with mine, to trigger a password reset yourself. Then you'll want to follow through on that email, and you'll be able to reset your password, and you'll have a little bit more confidence that this isn't a phishing attempt.

GT: Oh yeah, phishing, like how to tell if an email is legitimate, is a whole other topic for a future episode. But for right now, if you see an email out of the blue, and you don't recognize it, it's probably best to treat it with a little bit of suspicion.

LD: And then also make sure to tell your friends about this breach so that they update their passwords, too.

GT: You can also look up which known breaches your email account has been identified with at a website called haveibeenpwned.com.

LD: Oh, what a great website. It's so useful.

GT: You can sign up for future alerts, if your email address is ever seen in another breach notification. And we'll link the URL for that website in the notes with this episode.

LD: Yeah, let's take a quick break now before talking about how to manage all your unique passwords for your different online accounts.

Interlude music plays.

LD: And we're back. Let's talk about how to manage all those unique passwords you're going to start creating for all your online accounts.

GT: Assuming that you're not going to just memorize a bunch of completely unique passwords, you've got two good options: you can write them down in a physical notebook, or you can use some sort of digital password manager.

LD: You know, sometimes people make fun of those password notebooks you can buy at a stationery store that are really just like a ledger of account, date, and password, but really, they're not that bad. You've probably already found some physically secure location in your house, like for your birth certificate or your Social Security card, and you can also just put that password notebook in that place, too.

GT: And it's pretty unlikely that someone who's in your house is going to be able to just casually grab that notebook from that secure place.

LD: The biggest downside is that sometimes you aren't at home, and you're going to need your password. So either you're going to have to wait until you get home or you're going to have to carry some smaller set of your passwords in your wallet.

GT: And if you do that, definitely don't list what account they're for or the corresponding usernames.

LD: Maybe do some other ways of trying to make it a little harder, too. Like some people maybe put extra characters in their password that only they know aren't there. Or they have some extra passwords sprinkled in, so it's even harder to figure out what the right one is, you know, if you lose your wallet. None of these are really that great, though.

GT: The other major downside to the notebook approach is that you have to generate all the passwords yourself by hand, which as Liz mentioned earlier, can be a pain to do very well.

LD: And you also have to type in all those strong passwords manually. Like capital "T", "6", lowercase "p", "&" - I'm only four letters in, and I'm already kind of annoyed.

GT: Yeah, I think that's one of the biggest advantages of using a digital password manager: they can generate those strong passwords for you, and you probably won't have to type them in manually as much.

LD: Oh! And a lot of them can do more than just generate a generically strong password to use somewhere. They'll let you put in constraints about what kind of password you need. So maybe, you know, you're trying to make an account and it requires between 12 and 20 characters. It needs both lowercase and uppercase letters, but, you know, for this website, you can't use symbols and you do need a number - and it will generate a random password that is of the strongest type of password allowed within that set.

Before we talk more about different types of digital password managers, let's talk about why they're a good idea and what we should put in them.

GT: So one common objection I hear is: "Why should I trust this company to hold all of my passwords? You know, are they trustworthy and also doesn't that just put a big target on the company? Can someone just come and stealing all my passwords at once?" And the thing is, you're not really trusting them, this company, with all your passwords. The way that a password manager works is that there's a master password that you know and only you know. Every other password you have is stored encrypted, and the encryption key is that master password. So what you're really getting out of a password manager is the encryption software, and not so much a place to store all of your passwords.

LD: So you're not actually trusting whoever works at that company not to use your passwords, because they can't actually access them because they can't get past that encryption.

GT: Exactly, which is why you can keep all your passwords there safely, encrypted behind your master password. You just need to remember that one master password, and it does need to be strong. It's not like storing all your passwords in a file on Dropbox or somewhere, which is a thing I know some people do. If anything goes wrong with Dropbox - maybe you click share by mistake, maybe they mess up sharing (which has happened before), maybe any line of code anywhere at Dropbox stores backup a little too much or logs a little too much - then, suddenly, you've lost control of all your passwords. With a password manager, though, if something goes wrong, if that file gets leaked, it's still encrypted. You still have to choose a trustworthy company because you want to make sure their encryption software is safe, but it's way less risky than having a file with all your passwords somewhere on the internet.

LD: So if you forget your master password, you can't get any of your passwords back. You can't call up that company's tech support, because they don't have access either. They're just gone.

GT: Right, so this does not get you out of the business of memorizing passwords. But hopefully you only have to memorize a single, good password, and that one doesn't have to change very often. And every other password is just in your password manager.

LD: I actually want to push back a little bit on that idea that your password manager can have all your passwords, because I don't think that's true for most people. I mean, first, your workplace might not be okay with putting any of your work passwords in it.

GT: That's true. It depends on their culture, and maybe they already have a password manager program they use and licenses for it that you can use for your work accounts.

LD: Definitely, that's something you should ask them about! But also, I would never ever trust my password manager with my personal email account's password. Partly because it's really easy to wreak havoc on someone when they can pretend to be you with your email in a way that's not really as true in other accounts, but also because it gives someone access to pretty much every account you have online through password resets.

GT: Oh, that's a really good point. If something goes wrong and you lose access to your password manager, you're going to need to reset your passwords by email. So, first, you need to know your email password yourself so you can start resetting them without having access to your password manager. And second, if someone learns your master password for your password manager and they use that to take over your email account, then they can just change all of your passwords, including your email password, and you have no way back into anything. So for most people, I would say if you can remember one strong password for your password manager, you can probably figure out how to remember two unrelated, strong passwords, so that your email can be separate.

LD: Yeah. So now let's talk about different things you want to look for in a password manager.

GT: We're not really in the business on this show of recommending specific products, but we do generally want people to understand the tradeoffs they're making and what to look for. And also, in this particular case, there isn't a single, obvious right answer. Different password managers offer different features, and which one is best for me might not be what's best for you.

LD: One of your first concerns should be if it works well in the places that you're going to want to use it. Do you want to get access to your passwords on both your laptop and your phone? Do you sometimes use Windows and sometimes use a Mac? You want to see what integration is available for a specific password manager before you start using it. Lots of them will integrate directly into apps or your web browser. And if you always use the same web browser everywhere, that web browser's save password function might actually be a good choice for you, if that's what you're going to use.

GT: Yeah, if you're running Android on your phone and you only ever use Google Chrome on your computers, using Google for your password manager might work really well for you. If you do go that route, though, you should note that your Gmail password basically becomes your master password.

I actually didn't think about what I was going to use too carefully when I picked a password manager. I started using 1Password because that's what my last workplace used, and that's been great. But now I use Firefox on Linux these days, and 1Password does not have a browser plugin for Firefox on Linux yet. So, if you're like me and you use some uncommon browser or OS or some less common mobile phone platform or something, double-check what's supported, because it's way easier to have a browser plugin that just enters the password for you than to copy passwords from your mobile phone app and type them manually, which is what I'm doing these days.

LD: Having good integration into whatever your workflow is is really, really important because that means you're more likely to actually use it. And it's also going to be a lot easier for you to regularly change your passwords.

GT: Another thing to look for that we talked about earlier is that most password managers offer a strong password generator, including with the option to add in restrictions like Liz was mentioning earlier. And hopefully, it'll let you generate a password without storing it, so you can use it for your work account's password or for your personal email's.

LD: I think there are also two other nice-to-have features that you can look for, but they might not actually be essential for everyone. The first is the option to share passwords with someone else, like my partner and I both want to access the account for our electricity bill, and some password managers will automatically sync that between my password manager account and his.

GT: Some password managers have also started to offer a travel mode. When you activate that, it only keeps passwords you mark as safe for travel in your password manager app, and that might be really helpful for you if you travel to places and you're really worried about your phone getting stolen or broken into. Or it might not matter too much for you at all. It's definitely an added convenience, though, and you might find having a limited, safe set of passwords on your phone useful for cases other than just when you're traveling.

LD: And again, we're not here to endorse a specific product; there's a lot of really good ones out there. We want to make sure that you have the right information to make an informed decision that's going to work really well for you to handle your online account passwords. We both personally use digital password managers, but honestly, the best password manager is the one you reliably use.

GT: If you check out our website looseleafsecurity.com, we'll have links to popular password managers, so you can see which ones have the right features for you.

LD: And make sure that it's easy to change your password in the case of a breach, or, you know, just a once or twice a year for a security checkup.

GT: Next time, we'll talk about how to make your accounts even more secure with two-factor authentication, so that you're not just relying on passwords to keep your accounts safe.

LD: Spoiler! You should use it if you can, and preferably in a way that isn't tied to your phone number, but check back with us next time for a much more in-depth discussion.

Outro music plays.

LD: Loose Leaf Security is produced by me, Liz Denys.

GT: Our theme music, arranged by Liz, is based on excerpts of "Venus: The Bringer of Peace" from Gustav Holst's original two piano arrangement of The Planets.

LD: For a transcript of this show and links for further reading about topics covered in this episode, head on over to looseleafsecurity.com. You can also follow us on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook at @LooseLeafSecure.

GT: If you want to support the show, tell your friends about our podcast.

LD: See y'all next time for two-factor!

Outro music fades out.